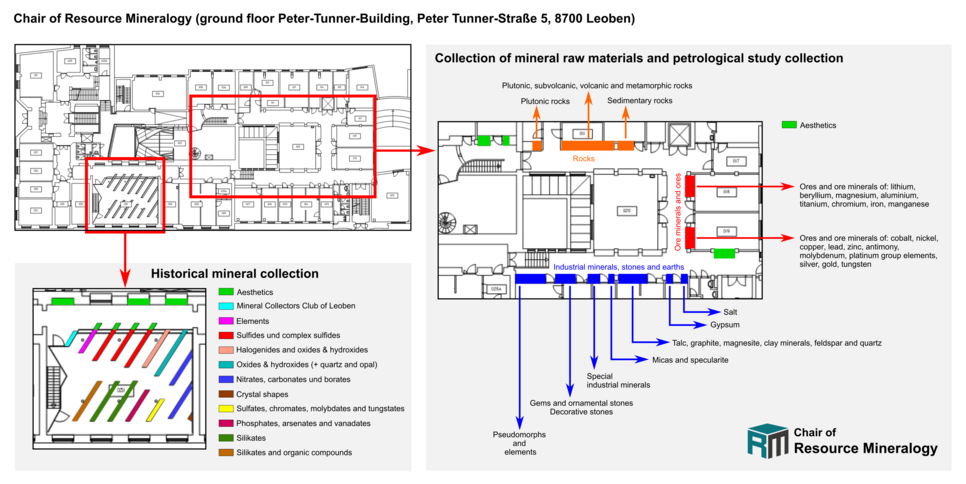

The Mineralogical Collection consists of historical mineral specimens, mineral raw materials, samples from academic theses, teaching collections, mounts and thin sections, and excursion samples from all over the world. The exhibition collection is part of this Mineralogical Collection and consists of a historical mineral collection, a collection of mineral raw materials and a petrological study collection:

The historical mineral collection can be visited by appointment, and the sample material in the Mineralogical Collection is available for scientific projects.

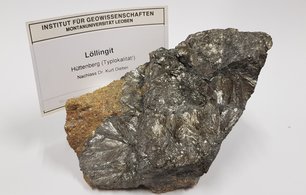

This extensive collection has also been enriched by specimens from several private collectors and former university members that have been added over the years.

Dr. Franz Dahlkamp

Dr. Kurt Dieber

Prof. Dr. Otmar M. Friedrich (mount collection)

Karl Goriup

Dr. Hellmuth Haas

Prof. Dr. Johann G. Raith

Reg.-Rat Franz Stockinger

Prof. Dr. Eugen F. Stumpfl